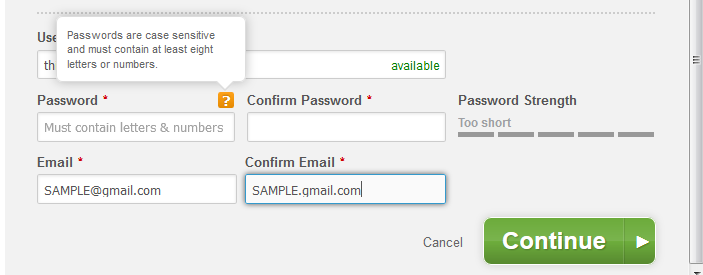

When you’re singing up with any online service, picking a password is always trouble. What weird password requirements does this service have? Tonight I had that question with Duke Energy’s sign-up form. Fortunately, they had a Help icon that described the password rules:

OK, minimum of 8 alphanumeric characters. Easy enough.

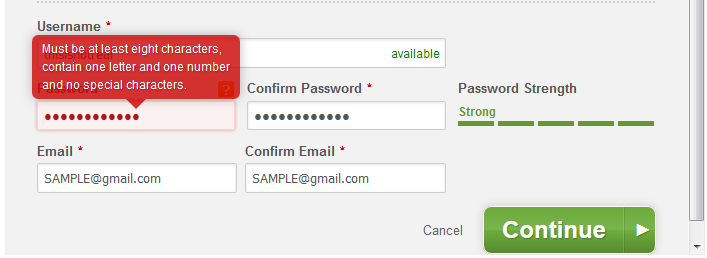

I use Password Safe as my password manager. I have no idea what any of my passwords are: they are auto-generated random strings. I generated a new random password and entered it into the form:

OK, so the password rules are a little different than what was initially described. But which symbols are special characters? And this screen is sending mixed-messages: if the password strength is rated Strong, why is it not valid?

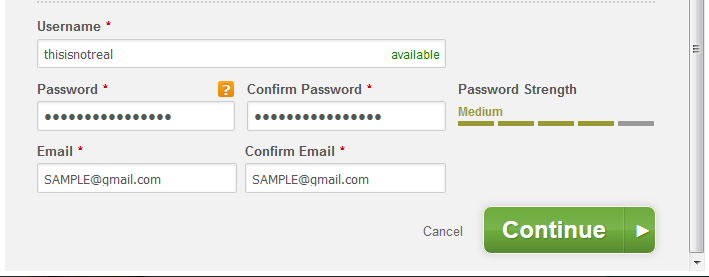

I updated the password generation rules in Password Safe to generate a new password, assuming that only alphanumeric characters are allowed:

- Use lowercase letters, minimum 1

- Use upper case letters, no minimum

- Use numbers, minimum 1

- No symbols

And, since no symbols are included, I increased the password length to 16 characters. This new password was accepted, but the feedback indicates that the password is only moderately strong!

I’m guessing that the code that generates the password strength indicator is from a 3rd-party and has no knowledge of Duke Energy’s password rules.

My problems with this, from a usability perspective:

- The password rules should apparent and described accurately.

- The password strength indicator should be aware of any password rules, and should describe a rejected password as such.

From a security perspective, I don’t see why any keyboard characters should be restricted. More characters to choose from means more complexity. Plus, if there were no character restrictions, it would be easier to describe the rules–and use an accurate 3rd-party password-strength tool.